by Graham J. Darling (as Doctor Carus of Burn Abbey); illustrations added by Rissa Johnson (as Lady Wymarcha Hektanah “Wendy” Doiron). First published in North Wind, 2012 Nov-Dec, n° 350, p 7-9.

Dear Doctor Carus,

This fortnight past I was at a holiday party, when Mr. Halitosis himself nearly trapped me under the proverbial sprig. I managed to escape with my virtue intact, but it got me wondering. Where and when did all this conjoining under poisonous shrubbery get started? Also, if holly is truly poisonous, what’s the sense in us “decking our halls” with it? Is there science or superstition behind the practice?

Unbesmirched,

Miss Elle Tow

My Lady Tow,

Congratulations on your deliverance from evil exhalation!

From seeds dropped by birds (from whence comes its common name, Anglo-Saxon for “dunged branch”), the European Mistletoe (Viscum album) parasitically sinks its roots high up on the trunks and boughs of many kinds of deciduous trees. The druids of Gaul would harvest it with golden sickles from sacred oaks [1]: because it showed green in midwinter amongst the bare branches of its host, it was to them (and many other peoples) a symbol of life and renewal under adverse conditions, and so they brewed or hung it to impart health, fortune and fecundity. Because it never touched dirty soil in the whole of its life-cycle, and was too flimsy to be made into weapons, mistletoe was also a symbol of purity, innocence and peace, even so that enemies would meet under it to parlay [2], and the goddess Frigg would omit it when she extracted oaths from all other things against harming her son Baldur the Beautiful (whom envious Loki eventually arranged to slay with a missile-toe)[3]. It was hung in houses from Yule to year’s-end to protect against fire, lightning and witchcraft [4]. So potent a charm it was against all manner of evil, that it protected Aeneas as he descended to the Land of the Dead to receive the destiny of Rome [5]. Its sticky white berries could be boiled down into the bird-lime of fowlers: association with such adhesive alchemy would further cement the bonds of gentle friendship and True Love. Alternatively, it’s been recently proposed that a mistletoe concoction could be employed as a contraceptive/abortificant following no-string flings [6], but, besides contradicting all other (albeit, non-evidential) medicinal traditions for this plant, Doctor Carus finds this idea as romantic as a bouquet of tied-off sheep intestines.

“Here were kept up the old games of hoodman blind, shoe the wild mare, hot cockles, steal the white loaf, bob apple, and snap dragon; the Yule-clog and Christmas candle were regularly burnt, and the mistletoe with its white berries hung up, to the imminent peril of all the pretty housemaids. (The mistletoe is still hung up in farm-houses and kitchens at Christmas, and the young men have the privilege of kissing the girls under it, plucking each time a berry from the bush. When the berries are all plucked the privilege ceases.)” [7]

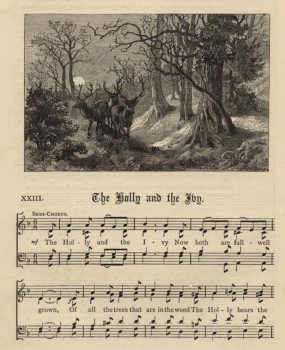

The European Holly (Ilex aquifolium) is another evergreen with which to deck the halls [9]. Its fruit, too, is toxic in seasons (Christmas is too early) and to animals not meant to spread its seeds (emetic though rarely fatal to omnivores like ourselves, but much more dangerous to dogs & cats)[10]. Besides similar general associations with survival and fidelity [11], holly has acquired additional meanings for Christians, as suggested by accounts of churches being decorated with it since the 15th century, and from the following popular carol [12] that may, in some form, date back to then:

The holly and the ivy, now are both well grown,

Of all the trees that are in the wood, the holly bears the crown.

Refrain

Oh, the rising of the sun and the running of the deer,

The playing of the merry organ, sweet singing in the choir.

The holly bears a blossom as white as lily flower,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ to be our sweet saviour.

(Refrain)

The holly bears a berry as red as any blood,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ to do poor sinners good.

(Refrain)

The holly bears a prickle as sharp as any thorn,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ on Christmas Day in the morn.

(Refrain)

The holly bears a bark as bitter as any gall,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ for to redeem us all.

(Refrain)

Merry Christmas from Brother Doctor Carus, and a happy and prosperous New Year to you all!

References:

1. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia/Natural History, 79 AD, book 16, ch 93-95; R. Goscinny & A. Uderzo Astérix le Gaulois, 1961.

2. W.C. Hazlitt Faiths and Folklore, 1905, p 412-413.

3. Snorri Sturluson “Gylfaginning”, Prose Edda, part 1, sec 50; A. Liberman “Some Controversial Aspects of the Myth of Baldr,” Alvíssmál, 2004, vol 11, p 17-54.

4. The Funk & Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend, 1950, vol 2, p 731-732.

5. Virgil The Aeneid, 19 BC, book 6; Sir J.G. Frazer The Golden Bough, 3rd Ed, 1922, ch 65 & 68.

6. J.R. Lee Natural Progesterone – The Multiple Roles of a Remarkable Hormone, 1993.

7. Washington Irving “Christmas Eve”, The Sketch Book, 1820; drawing on A Vindication of Christmas, 1652 and other early sources, and inspiring Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol, 1843, and the whole Victorian Christmas revival.

8. Br. François Rabelais Pantagruel, 1532, ch 11.

9. John Brand “Notes to Hagmena”, Popular Antiquities, 1777, rev 1841, vol 1, p 248-249.

10. N.J. Turner & P. von Aderkas The North American Guide to Common Poisonous Plants and Mushrooms, 2009, p 210.

11. The Funk & Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend, 1950, vol 1, p 501; Henry VIII Green Groweth The Holly, 16th C.

12. As collected from oral sources in H.R. Bramley & J. Stainer, Christmas Carols New and Old, Second Series, ca. 1871, n° 23; also, E.K. Chambers & F. Sidgwick, Early English Lyrics, 1907, p 374, mentions a 1710 manuscript containing this Refrain.